First Hearing in the Afrika Bambaataa Child Sex Trafficking Civil Case Set for November 1st

Is John Doe Safe? Court to Decide If He Can Remain Anonymous

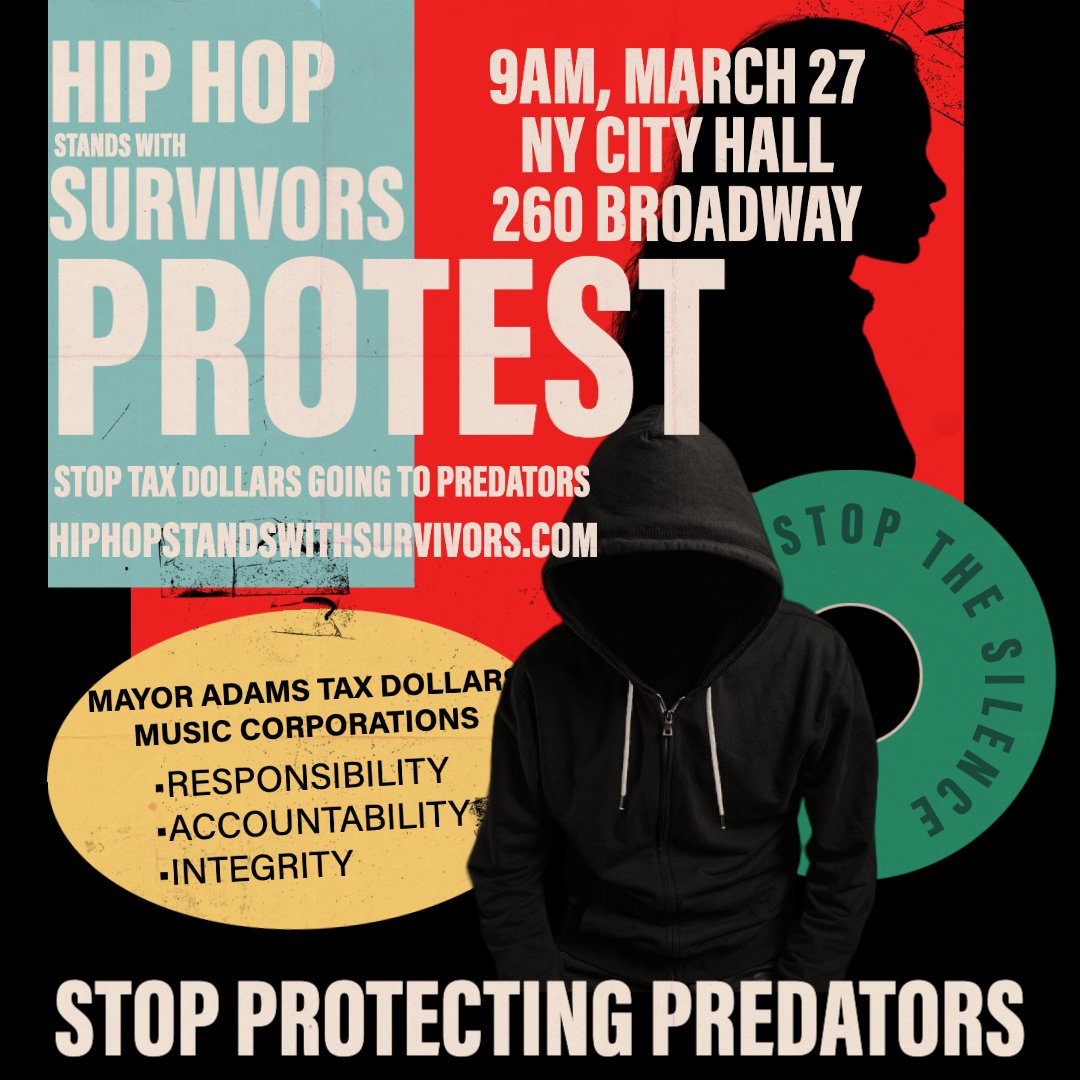

Art by Aya Downs

Bronx–Afrika Bambaataa is due in court via virtual conference on Monday, November 1, 2021, for the first hearing of the child sex trafficking lawsuit filed against him by a former member of his organization. Plaintiff attorney Hugo Ortega is requesting that the court allow anonymity in records and proceedings and the court has ordered Bambaataa to show cause on why it should not grant this request. Although Bambaataa and his attorney(s) would know the identity of the plaintiff, who is now using the pseudonym John Doe, a court order would ban them from revealing his name to the public and/or media.

On August 9, 2021, an unidentified man filed a civil lawsuit under the Child Victims Act (CVA) against Afrika Bambaataa, whose real name is Lance Taylor. In John Doe vs Lance Taylor, the plaintiff alleges hip hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa began sexually victimizing him as a twelve-year-old boy. It further alleges Bambaataa committed crimes of child sex trafficking by transporting the boy to different locations for other males to violate him in exchange for money. The suit also names the Zulu Nation as a defendant, a so-called hip hop awareness group that was founded by Bambaataa.

In criminal cases, anonymity is clear

Courts have afforded victims of sexual crimes the use of a pseudonym when there has been an investigation, arrest, or prosecution. Sexual offenses, by nature, are intimately sensitive violations that can attach long-lasting embarrassment and re-victimization once they become publicly known. Without privacy protection, victims could under-report, not cooperate with investigations and court proceedings. Because victims could fear coming forward, perpetrators may not get caught and sexual crimes could go unchecked.

Some defendants have challenged the Child Victims Act and issues of anonymity since its enactment. In 2019, New York Justice George Silver set a precedent in a CVA case against the New York Archdiocese when he upheld the same privacy provisions provided in criminal cases for the plaintiff in that civil case.

In his decision, Silver wrote, “To be sure, the legislature [regarding the CVA] wanted to avoid exposing alleged victims to the lasting scars of broadcasted exposure while ‘helping the public identify hidden child predators through civil litigation discovery, and shift the significant and lasting costs of child sexual abuse to the responsible parties.’ Considering the foregoing, it is axiomatic that plaintiff should be afforded the protection of anonymity.” Read Justice George Silver’s Decision

Stigma and embarrassment are compounded for male victims of sex crimes

Hassan Campbell at Bronx River Houses, Photo: Leila Wills

With Afrika Bambaataa, the stigma and embarrassment are compounded for the men who have made charges against Bambaataa because the alleged victims are Black and Latino males, most of whom identify as heterosexual men. Whispers of male-on-male sexual abuse are not even heard in some of these households and communities. But the allegations against Bambaataa forced these conversations into the public sphere. Male-on-male assault was something warned to protect against in jail, but not at home, church, or school. Even in the current social justice era and with the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, male victims of sexual assault say they have not found space.

In 2015, Hassan Campbell publicly accused Bambaataa of sexually abusing him, also beginning at 12 years old. While most of the listening public was sympathetic and outraged when his story came out, as time went by, some were not. Campbell identifies as heterosexual and for years, his detractors accused him of “wanting it” as a child and being homosexual as an adult. This had a chilling effect on other men, who wanted to corroborate the allegations against Bambaataa.

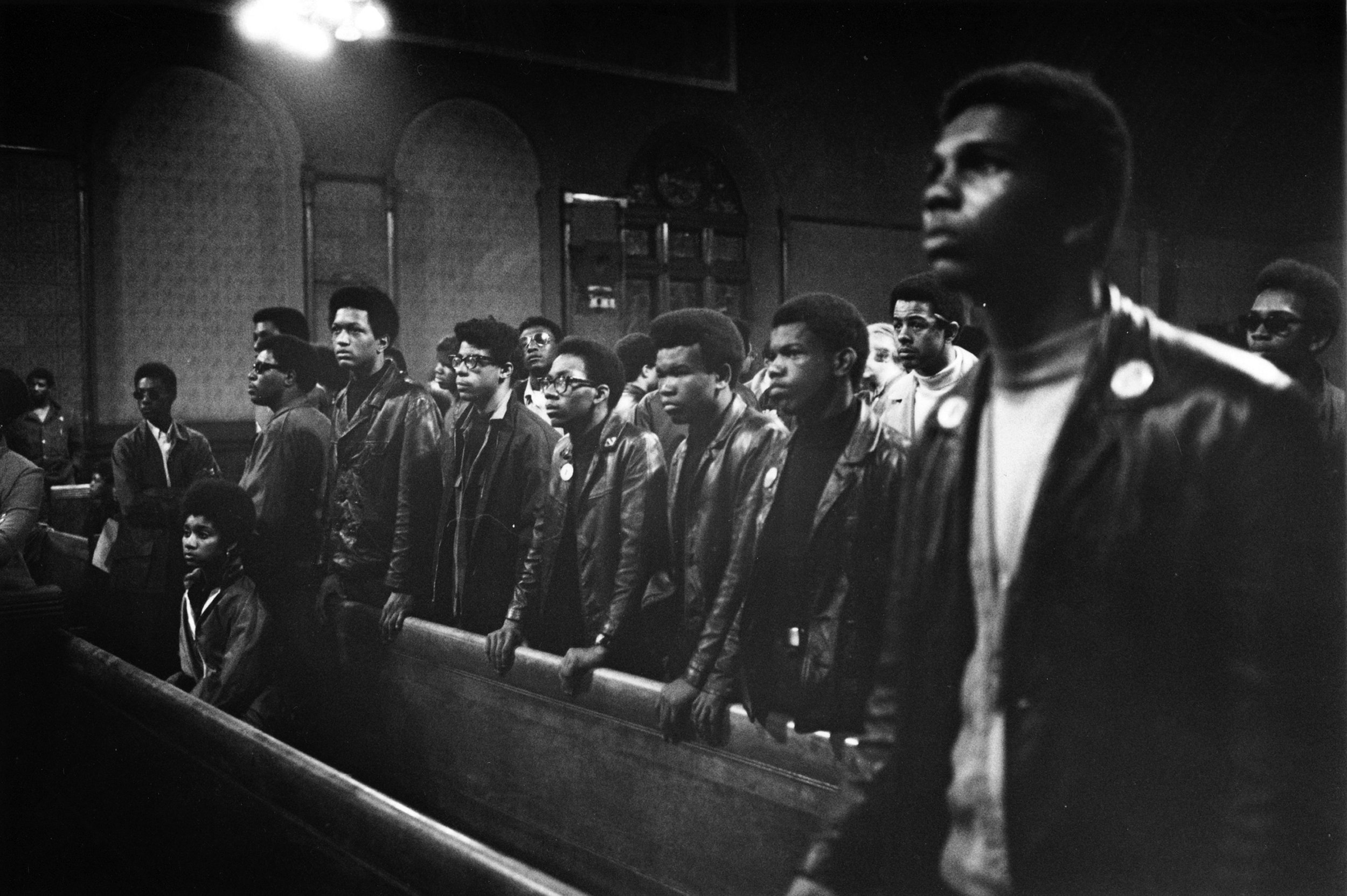

New York Times 1995

Intimidation

To make matters worse, most of the men who publicly accused Bambaataa of such heinous behavior knew all too well what could happen to them.

Hassan Campbell, and others who spoke under anonymity, openly discussed how “strong” the Zulu Nation was. Talking ill about Bambaataa could get you “seriously hurt,” Campbell stated.

These fears are not unfounded.

Bambaataa made his apartment in Bronx River Houses headquarters for the Zulu Nation.

The group/gang became so powerful that Bronx River Houses’ residents complained they were afraid and being held hostage by them.

In 1995, Mayor Giuliani and the NYPD launched an investigation and kicked them out of their Bronx River Housing base.

Watch Video of Zulu Nation Former International Spokesman TC Izlam: I Would’ve Been Dead

Grandmaster TC Izlam, whose real name is Tony Bell, allowed this writer to record him recounting death threats he received after speaking out against Bambaataa in 2017. An Atlanta man, Taleeb Paige, killed Izlam three weeks after the interviews and is serving 30 years without parole for his murder.

No one identified Paige as a member of the Zulu Nation or as an affiliate of Bambaataa and neither was charged in that crime. Yet, Izlam’s murder had paralyzing reverberations on the alleged victims and others who had not come forward.

The climate intensified by several degrees as rumors spread about his killing.

John Doe’s Safety

Afrika Bambaataa in 1995, Photo: Getty Images

In an affidavit filed on August 10, 2021, John Doe said his request for anonymity primarily comes out of fear for his life. The affidavit reads in part, “My concerns with being identified go beyond the ordinary reticence to be identified as a victim of sexual abuse or as an object of sex trafficking. Though I certainly would prefer not to be the subject of that kind of unwelcome attention, my real concern is with my personal safety. I and many other victims of the defendant have been in fear of the consequences if we speak out...I also fear for my life.”

Continuing, John Doe stated, “...he [the defendant] has affiliates who may take direct action to stifle attacks.”

In 2013, a stabbing allegedly took place. The incident involved a young man who, according to several sources close to Bambaataa, was approximately 18 or 19 years old. One source had seen the teen at parties and other Zulu Nation functions.

A rumor circulated that Bambaataa had drugged and date-raped the teen. When the teen woke up to Bambaataa performing oral sex on him, he began stabbing him. The exact details of what took place that night were sketchy, and Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation publicly denied a stabbing had taken place.

Interestingly, and also very concerning is that this writer spoke to four members of the Zulu Nation and all said that Bambaataa passed out information on the young man in addition to the teen’s picture with unspoken orders to “handle the situation” and “get rid” of him.

Writer and author Khalil Amani published a story about the stabbing. A few days later, Amani received a call from an industry insider who said the Zulu Nation was not happy about the article. One person contacted Amani directly and said, “You know you can be touched, right?” He took the article down but reposted it a few days later.

Journalist and best-selling author Dave Wedge wrote an extensive piece on the allegations against Bambaataa. He and his partner, Casey Sherman, recently published two episodes on Bambaataa on their podcast, Saints, Sinners and Serial Killers. He too says a Zulu Nation soldier threatened him.

If the court grants John Doe anonymity from the public and media, Bambaataa would still know his true identity. What would stop him from alerting his top soldiers, many of whom surround him to this very day? Are there any other remedies for John Doe?

Justice George Silver was to preside over the John Doe vs Lance Taylor, aka Afrika Bambaataa, hearing on November 1, 2021. He retired from the New York Supreme Court on September 30, 2021.

The likelihood of Silver’s replacement to rule against his decision for privacy protection for victims is extremely low. Silver’s decision to uphold the use of a pseudonym by alleged victims of sexual abuse in civil proceedings has affected thousands of cases.

As of now, Bambaataa has no attorney on record and has made no filings with the court. The real questions are; will he show up on November 1st and how can John Doe stay safe while pursuing justice? Metropolis